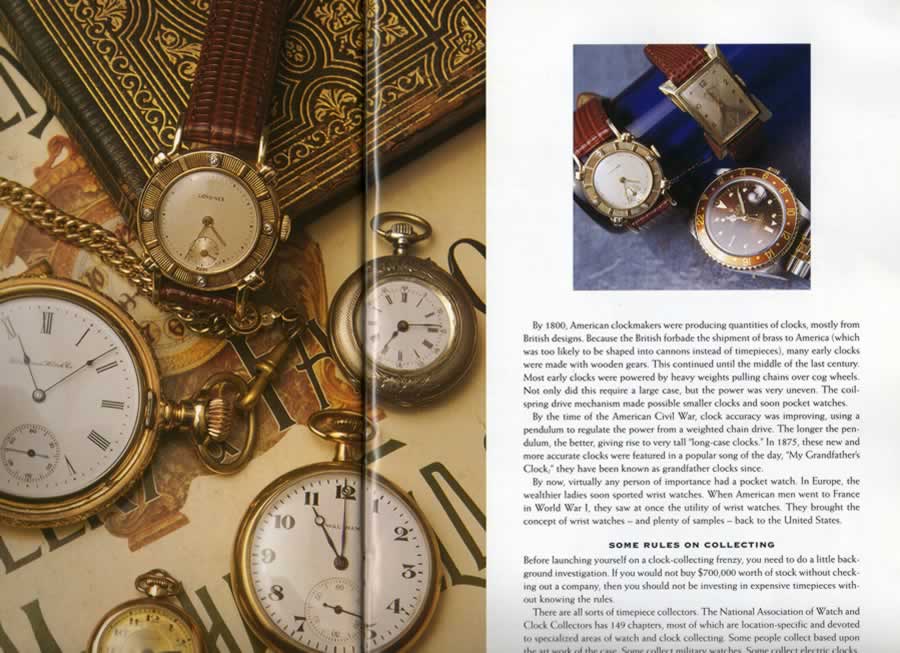

Most early clocks were powered by heavy weights pulling chains over cog wheels.

Not only did this require a large case but the power was very uneven. The coil-spring

drive mechanism made possible smaller clocks and soon pocket watches. Some wrist

watches even today are powered by coil springs.

By

the time of the American Civil War, clock accuracy was improving, using

a pendulum to regulate

the power from a weighted chain drive. The longer

the pendulum the better, giving rise to very tall 'long-case clocks'.

In 1875, these new and more accurate clocks were referred to in a popular

song of the day, 'My Grandfather's Clock' and they have been

known as grandfather clocks since.

By now virtually any person of importance had a pocket watch and in Europe

the ladies soon sported—if they were wealthy enough—wrist watches.

When American men went to France in World War One, they saw at once the

utility

of wrist watches and brought wrist watches, and the concept of plentiful

and cheap wrist watches, back to the United States.

Before launching yourself on a clock-collecting frenzy, you need to do

a little background investigation. If you would not buy $700,000 of stock

without checking out a company, then you should not be investing in expensive

timepieces without knowing the rules:

Decide Upon A Collecting Technique

There are all sorts of timepiece collectors. The National Association of

Watch and Clock Collectors has 149 chapters, most being geographic specific

but many being devoted to specialized areas of watch and clock collecting.

Some people collect based upon the art work of the case. Some collect military

watches. Some collect electric clocks. There are devotees of 400-day clocks

and others collect early American watches.

Where to start collecting? Go buy something, almost anything. Experience

the thrill of the chase and the gloat of the ownership. Then refine your

collection as your knowledge increases. Here are some rules:

• Educate yourself. This is half the fun and indispensable before you start

to write any big checks. There are books, clubs, auctions, many places

to learn more about collectible timepieces. Subscribe to auction house

catalogues, they can be wonderful tools for developing your 'eye'. Sotheby's,

just for example, publishes over 120 catalogues a year in the U.S. alone.

• Go to auctions. If you know your way around you could probably find bargains

at the local flea market. If you want a little help, the major auctions

will not only guarantee—as much as such things can be guaranteed—the

authenticity and value of the items, but they often sell by sets or periods

or collecting areas, making it easier for you to add to your collection

in a rational manner.

• Consider collecting at the second-tier. This is popular with the deep

checkbook collector. If 18th Century French mantlepiece clocks are all the rage,

that means all the good ones are soon going to be out of circulation. This

in turn will promote the next most popular item to the top spot. The trick

is to figure out just what the second-tier is for your particular collecting

area—and then buy up quality stock before your competitors make the

same calculation. Hope you were right, or you have only committed a very

expensive

form of 'contrarian' buying.

• Contrarian buying. This technique is especially popular among collectors

with enthusiasm but small budgets. Buy what no one else is buying and which

is correspondingly cheap. Then hope the popularity cycle will come around

to your way of thinking. This is not as silly as it sounds, given that

almost every style of timepiece has had its hour; the only real question

is, how long will you or your descendants have to wait? Contrarian buying

is also most useful if you collect deep, not wide.

• Collect deep, not wide. A collection of individual expensive timepieces

that have no relation to one another is just that and no more. But the

narrower the focus of your collection—assuming that you can assemble such

a narrow focus—the more valuable the collection becomes as a whole,

perhaps far exceeding the total value of the individual items. This assumes,

of

course, that at some point you sell the collection as a whole, and don't

break it up. A recent auction of a collection of 16 pocket watches made

by one Danish watchmaker from 1860-1905 fetched $325,230, about $20,300

per item. Was each item in the collection worth that much individually?

Probably not.

• Buy quality, not quantity. Buy one of the best timepieces that maker

made, and not ten of his cheaper models. The best of any collectible will appreciate

in value even in a recession, while cheaper collectibles are more subject

to the ups and downs of the overall economy.

Choose Your Purchases Carefully:

Timepiece collectors need to assess the authenticity of each purchase and

need to buy smart so as to create a collection whose value transcends that

of the individual items. Here are some general rules to follow:

• Age: As a general rule the older the timepiece the more expensive. Hardly

a surprise, and most likely intertwined with rarity and condition, below.

Experts can usually assess the age of any mechanical timepiece to within

10 or 15 years, based upon details of the mechanism and of the case.

• Authenticity: The more obvious the clue, the easier to fake. Paperwork

can be wholly invented. Labels that are painted on or riveted on might

have been added later. Additional artistic details can be retrofitted onto

an otherwise plain longcase clock to artificially increase its value. Conversion

kits to convert clock movements from their original construction to something

else have been around almost as long as the clocks themselves. A beginning

collector is in no position to detect any but the most blatant fakery;

buying from reputable dealers and having the timepiecechecked by a knowledgeable

person is the best insurance.

•

Married elements: Related to authenticity, many clocks have "married

elements" in which the case, the dial, and the movement may come from

different times, countries, or makers. Sometimes this was done to preserve

an older movement by replacing the damaged case. Sometimes it was the case

that was preserved and a newer and more accurate movement substituted.

Most often the owner liked the case but tired of having to wind the clock

so often and so installed a movement requiring less frequent maintenance,

see 'conversion kits' under Authenticity, above. The marriage might be

obvious or not, but one thing that is certain is that a "married" clock

is virtually useless as a collectible.

• Condition: At first blush you would assume that it's better to have a

watch in perfect condition, or a longcase clock with no mars on the fine wood.

But time takes its toll, even on timekeepers. Wooden feet rot, paint flakes

off of dial faces, cases get dented and glass broken. Almost any older

watch , pocket watch or clock has had some restoration. But beware the

sloppy repair job which can do more damage to the value—especially the

historic value—of the item than the original damage.

• Quality: In any age, some timepieces were better-made or better decorated—and

thereby more expensive—than others. Quality is not to be confused

with workmanship, as defined below.

• Workmanship. Even Michelangelo's chisel slipped occasionally and the

finest watchmaker has had a bad day or two. But overall, workmanship with timepieces

is fairly even within a line or by a particular maker.

•

Rarity: This is obvious. The one and only pocket watch produced by a company

famous for making wristwatches would be worth far more than its weight

in gold. One "Swatch Watch" today would be worth about as much

as a—well—a swatch watch. It's precisely because most timepieces

today are mass-produced that collectors tend to look to the past, when

timepieces

were individually crafted, for value.

•

Historic Importance: The most uninteresting watch in the world would be

worth more if it is connected with a famous person and/or a famous event.

Be forewarned that the historic importance is often determined by the provenance,

the documentation that accompanies the piece. See "Authenticity," above

and remember that enough slivers of the True Cross have been sold over

the centuries to build a monastery.

• Artistic details: As a broad general rule the more 'fancy' the timepiece

the higher value it will command, simply because people like to look at

art work. Until recent times of course, almost all clocks and watches were

also regarded as art work. Some early American clock cases were severely

plain but of very fine wood and with either rare American clockmakers'

timepieces installed or more common British mass-produced imports. French

cases of the same period matched period furniture, being quite Baroque

at times. British styles fell somewhere in the middle, as befitted a Victorian

society. Sometimes the art work needed to produce the cases for clocks

and even pocket watches far exceeded in workmanship, detail, and sheer

manpower, that needed to produce the actual mechanism.

• Popularity: What's in fashion in today's collectible market? What do

you think will be in fashion tomorrow? If all you want is a fast turnover for

maximum profit, the trick is to buy for peanuts today what will sell for

cashews tomorrow. Most of us lack the requisite crystal ball to make that

determination and all the economists in the world can't tell us what will

be the most popular collectible timepieces next year.

Maintain Your Collection

Take good care of your collection. Timepieces are what museum curators

call "compound" items, meaning they have parts made of very different

materials, each requiring a different preservation technique. Don't preserve

that wooden case with a chemical that corrodes the metal clock movement,

or use a glass cleaner that rots or discolors the wood finish. Most collectors

keep their smaller clocks, pocket watches and wristwatches in special cases

or under glass covers to stabilize the environment.

Also keep all paperwork relating to each item in your collection. It's

easy to let this slide and later find you have more items in your collection

than you have paperwork to accompany them. This can lower the value of

the collection.

Pay attention to sales of similar items and add that information to your

paperwork against a later day when you decide to sell.

And you will sell. In addition to the thrill of the hunt and the pleasure

of ownership, there is the satisfaction of selling for a good profit, or

even to get the money needed to buy a different timepiece. You will find

the grass is always greener over there, someone else has already taken

the brown egg, and your new friend has the very clock you need to complete

your collection—if only you can find someone to buy this pocket watch

you have tired of. In the end, clock and watch collectors are really only

baseball card traders who grew up.

— end — |